BRandon Yu

San Francisco Chronicle, August 6, 2021

When Al Perez immigrated, along with his five siblings, to San Francisco from the Philippines in 1980 at the age of 13, reuniting with parents who had arrived six years earlier, overt racial discrimination was commonplace. So growing up, he says, he was taught to assimilate.

“We were encouraged to be as American as possible,” recalls Perez, the president of Filipino American Arts Exposition, a San Francisco cultural nonprofit. “We spoke (only) English at home. I don’t even remember having any Filipino decor growing up in my old house here. Over time, I sort of lost my ability to speak Tagalog.”

It wasn’t until well into his adulthood that Perez, struggling to find a way to reconnect to his culture, was introduced by a friend to the Pistahan Parade and Festival, the annual Filipino celebration and gathering in the city. The local event needed someone to help design a poster, and Perez, an art director for Bank of America’s Creative Services Department in San Francisco at the time, took up the task.

That volunteer gig turned into an annual appointment for Perez that offered him a way to connect with his Filipino heritage, and led to his eventually becoming the president of FAAE, the organization behind Pistahan.

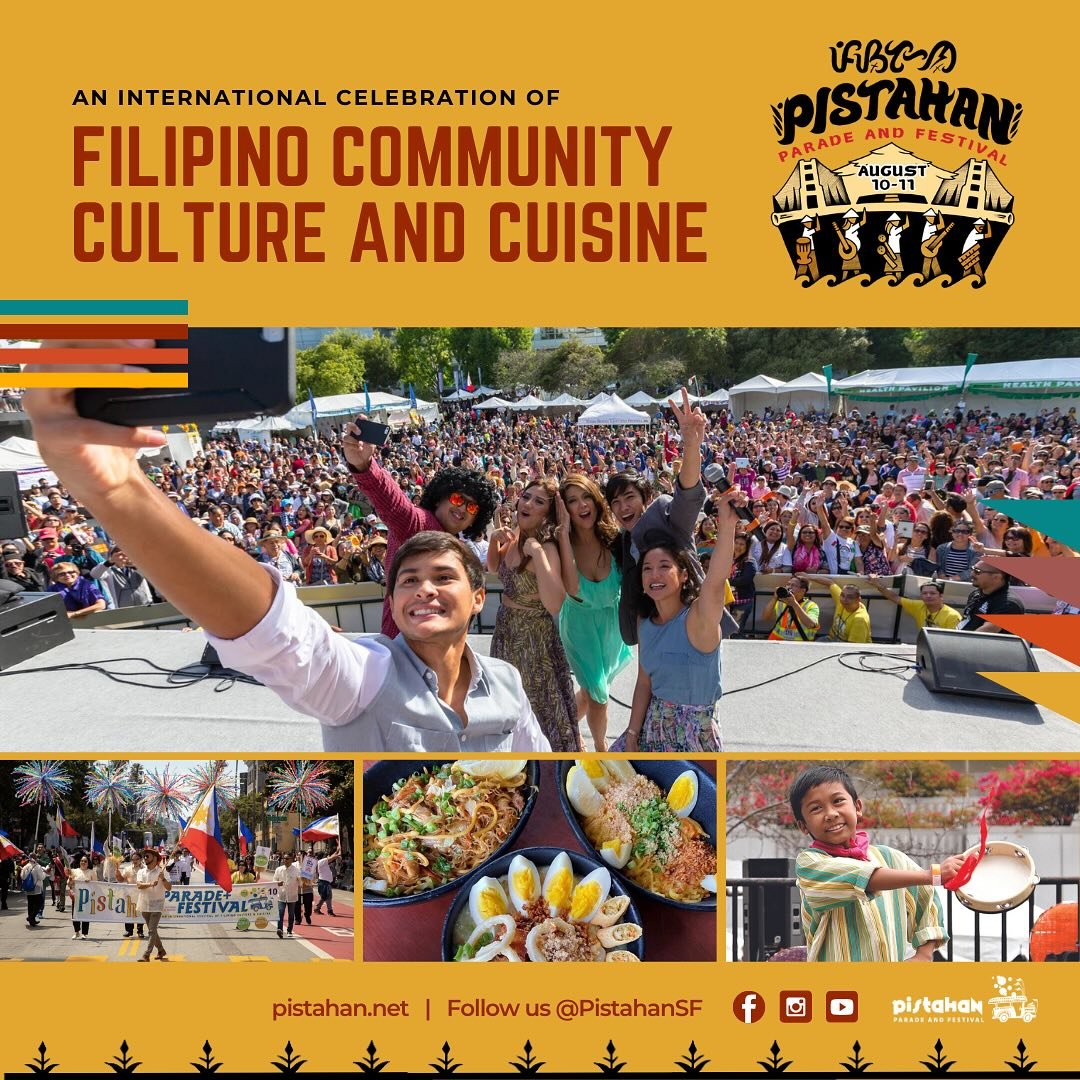

Like last year’s festival, the upcoming 28th edition will be celebrated virtually (via Facebook Live and Youtube Live, along with Kumu, a Filipino live-streaming platform) on Saturday and Sunday, Aug. 14-15. It aims to continue providing a spotlight on the Filipino and Filipino American community, not just in the Bay Area but also around the world — just as it did when Perez first attended in 2002.

“When I first started, just coming together and seeing a lot of other brown people together — a lot of people like me — (there’s) something empowering about that,” he says.

That spirit of pride and reclamation is the foundation upon which Pistahan, which translates to “feast” or “festival” in Tagalog, was built. It’s also what helps the event to persist despite the various struggles of the past year and a half, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise in anti-Asian violence.

Pistahan (pronounced PEE-stah-hahn), which ordinarily features a parade and pavilions celebrating Filipino culture, cuisine and history, was created to honor two events that encapsulate the resilience of San Francisco’s Filipino and Filipino American community: the infamous International Hotel battle and eviction in 1977, which essentially erased the remnants of the city’s historic Manilatown, and the displacement years later of some 4,000 Filipino families by the redevelopment of Moscone Convention Center and Yerba Buena Gardens.

“In a way I kind of think of it as our way to reclaim our land when we go back to Yerba Buena Gardens,” Perez says of the event, which, before the pandemic, took place there each year. “A community was there. We used to be there.”

Pistahan has also always taken place on the second weekend of August because “we lost the I-Hotel in the first weekend of August,” Perez explains. “Now we have a way to gain something back with a celebration.”

As it was for Perez, Pistahan has always served as a cultural bridge for the diaspora. Many attendees were born in the Philippines, says Vanessa Garcia, who is slated to host this year’s Culinary Pavilion, while “the younger folks who are born here are not struggling, they really are thirsty for being in touch with the Filipino culture.”

Filipino pride has surged in the past decade, according to Garcia, boosted by the international success of those like famed boxer and politician Manny Pacquiao, comedian Jo Koy, and most recently Hidilyn Diaz, a weightlifter who won the first-ever Olympic gold medal for the Philippines in the Tokyo Games last month.

Like all public events, Pistahan has had to adjust sharply to the health concerns raised by the pandemic. Just as it did last year, this August’s festival, whose theme is “Renew, Recover and Rise Together,” will live-stream a mix of prerecorded performances and showcases. While many organizations have begun to return to outdoor gatherings, Perez’s team decided to remain online only, a choice informed by concern for a community — including many health care professionals and restaurant workers — that has been particularly besieged by COVID-19.

The mortality rate from the disease is disproportionately high among Filipino health care workers, Perez notes; nearly one third of all nurses who have died from COVID-19 in the U. S. were Filipino. The pandemic was an unending roller coaster for Garcia and her team at the 7 Mile House restaurant in Brisbane. Her restaurant was forced to close for a month and a half before shifting to takeout-only service. She also relied on donations as her staff navigated the constant changes to dining restrictions.

And yet, there were also bright spots, Garcia said. She was heartened to see the community come together to support her restaurant; longtime patrons helped organize fundraisers and provided everything from masks and sanitizers to bay leaves needed for dishes like pork adobo.

This year, Pistahan will honor the sacrifices of health care workers at its virtual Health Pavilion, and will coordinate with local Filipino restaurants to compile an online directory, encouraging virtual attendees to buy food from them while tuning into the live stream.

For Perez, pivoting the festival to the virtual space meant an opportunity to broaden the scope of both its audience and participants. Last year’s festival included performers and presenters streaming from the Philippines as well as Australia, Canada and Dubai, among other far-off locales. And the festival was viewed in 34 countries.

This year’s Pistahan “parade” will be a montage of videos submitted from around the world, showcasing costumes, dances and Filipino cuisine. One theme will unite all the submissions: Each presenter will end their video with a message written on their palm: Stop Asian Hate.

“By showing our culture to other communities, we hope that there will be more understanding,” Perez says. “We’ve gone through a lot of traumas and struggles in the past, and we just need to remember that that’s what the community is for, to support each other.”

Brandon Yu Brandon Yu is a Bay Area freelance writer.